Feynman's Dead Wife, Schrodinger's Dead Cat, and the Death of the Golden Age of Physics

Feynman and Schrodinger both had amazing insights into not only physics, but many aspects of life.

Richard Feynman's first wife died when she was 25 from tuberculosis. He wrote her a letter that remained sealed until his death 40 years later. I read it a few years ago and it has stuck with me.

Richard Feynman's first wife died when she was 25 from tuberculosis. He wrote her a letter that remained sealed until his death 40 years later. I read it a few years ago and it has stuck with me.

- - - - - - -

D’Arline,

I adore you, sweetheart.

I know how much you like to hear that — but I don’t only write it because you like it — I write it because it makes me warm all over inside to write it to you.

It is such a terribly long time since I last wrote to you — almost two years but I know you’ll excuse me because you understand how I am, stubborn and realistic; and I thought there was no sense to writing.

But now I know my darling wife that it is right to do what I have delayed in doing, and that I have done so much in the past. I want to tell you I love you. I want to love you. I always will love you.

I find it hard to understand in my mind what it means to love you after you are dead — but I still want to comfort and take care of you — and I want you to love me and care for me. I want to have problems to discuss with you — I want to do little projects with you. I never thought until just now that we can do that. What should we do. We started to learn to make clothes together — or learn Chinese — or getting a movie projector. Can’t I do something now? No. I am alone without you and you were the “idea-woman” and general instigator of all our wild adventures.

When you were sick you worried because you could not give me something that you wanted to and thought I needed. You needn’t have worried. Just as I told you then there was no real need because I loved you in so many ways so much. And now it is clearly even more true — you can give me nothing now yet I love you so that you stand in my way of loving anyone else — but I want you to stand there. You, dead, are so much better than anyone else alive.

I know you will assure me that I am foolish and that you want me to have full happiness and don’t want to be in my way. I’ll bet you are surprised that I don’t even have a girlfriend (except you, sweetheart) after two years. But you can’t help it, darling, nor can I — I don’t understand it, for I have met many girls and very nice ones and I don’t want to remain alone — but in two or three meetings they all seem ashes. You only are left to me. You are real.

My darling wife, I do adore you.

I love my wife. My wife is dead.

Rich.

PS Please excuse my not mailing this — but I don’t know your new address.

D’Arline,

I adore you, sweetheart.

I know how much you like to hear that — but I don’t only write it because you like it — I write it because it makes me warm all over inside to write it to you.

It is such a terribly long time since I last wrote to you — almost two years but I know you’ll excuse me because you understand how I am, stubborn and realistic; and I thought there was no sense to writing.

But now I know my darling wife that it is right to do what I have delayed in doing, and that I have done so much in the past. I want to tell you I love you. I want to love you. I always will love you.

I find it hard to understand in my mind what it means to love you after you are dead — but I still want to comfort and take care of you — and I want you to love me and care for me. I want to have problems to discuss with you — I want to do little projects with you. I never thought until just now that we can do that. What should we do. We started to learn to make clothes together — or learn Chinese — or getting a movie projector. Can’t I do something now? No. I am alone without you and you were the “idea-woman” and general instigator of all our wild adventures.

When you were sick you worried because you could not give me something that you wanted to and thought I needed. You needn’t have worried. Just as I told you then there was no real need because I loved you in so many ways so much. And now it is clearly even more true — you can give me nothing now yet I love you so that you stand in my way of loving anyone else — but I want you to stand there. You, dead, are so much better than anyone else alive.

I know you will assure me that I am foolish and that you want me to have full happiness and don’t want to be in my way. I’ll bet you are surprised that I don’t even have a girlfriend (except you, sweetheart) after two years. But you can’t help it, darling, nor can I — I don’t understand it, for I have met many girls and very nice ones and I don’t want to remain alone — but in two or three meetings they all seem ashes. You only are left to me. You are real.

My darling wife, I do adore you.

I love my wife. My wife is dead.

Rich.

PS Please excuse my not mailing this — but I don’t know your new address.

- - - - - - -

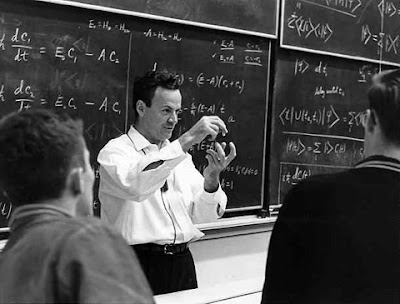

Feynman is most known for his magnificent lectures, his work on the Manhattan Project, and winning the Nobel Prize for his work in electrodynamics and quantum physics. I like "The Meaning of it All". In that book, which are transcribed speeches, he really delves into deep things about the division between science and religion, and his wisdom really shines forth. Here are just two great paragraphs.

- - - - - - -

And finally I would like to make a little philosophical argument—this I'm not very good at, but I would like to make a little philosophical argument to explain why theoretically I think that science and moral questions are independent. The common human problem, the big question, always is "Should I do this?" It is a question of action. "What should I do? Should I do this?" And how can we answer such a question? We can divide it into two parts. We can say, "If I do this what will happen?" That doesn't tell me whether I should do this. We still have another part, which is "Well, do I want that to happen?" In other words, the first question—"If I do this what will happen?"—is at least susceptible to scientific investigation; in fact, it is a typical scientific question. It doesn't mean we know what will happen. Far from it. We never know what is going to happen. The science is very rudimentary. But, at least it is in the realm of science we have a method to deal with it. The method is "Try it and see"—we talked about that and accumulate the information and so on. And so the question "If I do it what will happen?" is a typically scientific question. But the question "Do I want this to happen"—in the ultimate moment—is not. Well, you say, if I do this, I see that everybody is killed, and, of course, I don't want that. Well, how do you know you don't want people killed? You see, at the end you must have some ultimate judgment.

You could take a different example. You could say, for instance, "If I follow this economic policy, I see there is going to be a depression, and, of course, I don't want a depression." Wait. You see, only knowing that it is a depression doesn't tell you that you do not want it. You have then to judge whether the feelings of power you would get from this, whether the importance of the country moving in this direction is better than the cost to the people who are suffering. Or maybe there would be some sufferers and not others. And so there must at the end be some ultimate judgment somewhere along the line as to what is valuable, whether people are valuable, whether life is valuable. Deep in the end— you may follow the argument of what will happen further and further along—but ultimately you have to decide "Yeah, I want that" or "No, I don't." And the judgment there is of a different nature. I do not see how by knowing what will happen alone it is possible to know if ultimately you want the last of the things. I believe, therefore, that it is impossible to decide moral questions by the scientific technique, and that the two things are independent.

You could take a different example. You could say, for instance, "If I follow this economic policy, I see there is going to be a depression, and, of course, I don't want a depression." Wait. You see, only knowing that it is a depression doesn't tell you that you do not want it. You have then to judge whether the feelings of power you would get from this, whether the importance of the country moving in this direction is better than the cost to the people who are suffering. Or maybe there would be some sufferers and not others. And so there must at the end be some ultimate judgment somewhere along the line as to what is valuable, whether people are valuable, whether life is valuable. Deep in the end— you may follow the argument of what will happen further and further along—but ultimately you have to decide "Yeah, I want that" or "No, I don't." And the judgment there is of a different nature. I do not see how by knowing what will happen alone it is possible to know if ultimately you want the last of the things. I believe, therefore, that it is impossible to decide moral questions by the scientific technique, and that the two things are independent.

- - - - - - -

Erwin Schrodinger was also a great physicist. He's most know for Schrodinger's Cat. That's the thought experiment where a cat is in a box with poison and the cat is considered both alive and dead. Most people misunderstand the point of that thought experiment. Schrodinger was pointing out that the idea that the cat is both alive and dead at the same time is stupid.

He was another great physicist also full of greater depth and wisdom. I especially like his "Mind and Matter" and "What is Life?". In "What is Life?" he presents the idea that life is a negentropic system, or anti-entropic system, or the opposite of things falling apart. (This is similar to the ideas of syntropy, free energy, and Hans Hass's energon.)

Physics has seen its golden age come and go, and maybe its golden physicists as well. Luckily they left a body of work that we can still mine for wisdom.

________________________________________________

You can find more of what I'm doing at http://www.JeffreyAlexanderMartin.com

Comments

Post a Comment